A new method for whole Zika virus sequencing

We calculated that to make generating 1000 genomes a realistic target in the time frame of a few months at a sensible price per genome we would need to sequence about 12 samples per MinION flowcell. To do this you need to sequence mostly on-target reads, this was same in Guinea but for different reasons, there we were limited by upload speed and here throughput. In contemplating how to generate somewhere around 480 amplicons per run (assuming 40 amplicons x 12 samples) we realised we needed some kind of multiplexing strategy. Nick had the idea to use a Fluidigm access array which has about 2000 9 nl reaction chambers in a custom microfluidic consumable designed exactly for doing highly parallel single-plex PCR reactions. Looking into it I think it probably would have worked but additional equipment including a loader/unloader for both pre- and post-PCR was needed in addition to the thermocycler. We guessed it would have cost in the region of $50k to equip the bus which was too expensive and not scaleable if more collaborating laboratories came on board later.

We were left with a multiplex PCR scheme something like a home-made AmpliSeq which allows up to 1536 reactions in the same tube. We didn’t really want to pay for it though as it came in at a hefty $50 per sample but we thought the concept itself was great. Nick and I took a look at the protocol and a couple of things stood out. Firstly the PCR cycling conditions are two step i.e. if you have primers with Tm’s around 65°C, you can just combine both the annealing and extension steps into one. In this case the 65°C step was 15 minutes per cycle! Given that the panels are designed to have a maximum product length of 375 bp it’s obviously not the DNA polymerase that needs that long to extend (usually 1 min/kb) so I figured it must be to allow primer annealing. We thought maybe the primer concentration was very low to create a self-limiting system which balances the abundance of products generated.

Our initial attempt used software called PriMux (http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0034560) to generate a scheme. The software generates all k-mers of specified length for all specified reference genomes then picks the most conserved and filters for desired characteristics (i.e. Tm, product length, position). We specified k=18 and a Tm range of 63-67 and it generated a scheme, however it was missing primers for some positions where there were none meeting the specified criteria. We chose those values because we thought the shortest possible primers would have fewer mismatches, and the high Tm as we wanted to avoid non-specific amplification and primer-primer interactions. In retrospect it was a mistake to use such a short length as primers of this length and Tm are invariably stronger bonded GC rich sequences biasing the selection. It strikes me as a limitation of k-mer based methods that you may need to specify a range of k-mers otherwise the primers are limited to sequences of the same length regardless of GC content. In order to give ourselves more options for primer combinations in the field we ordered a 400 bp and a backup 200 bp scheme, both with a 100 bp overlap. With alternates, it totalled 450 primers!

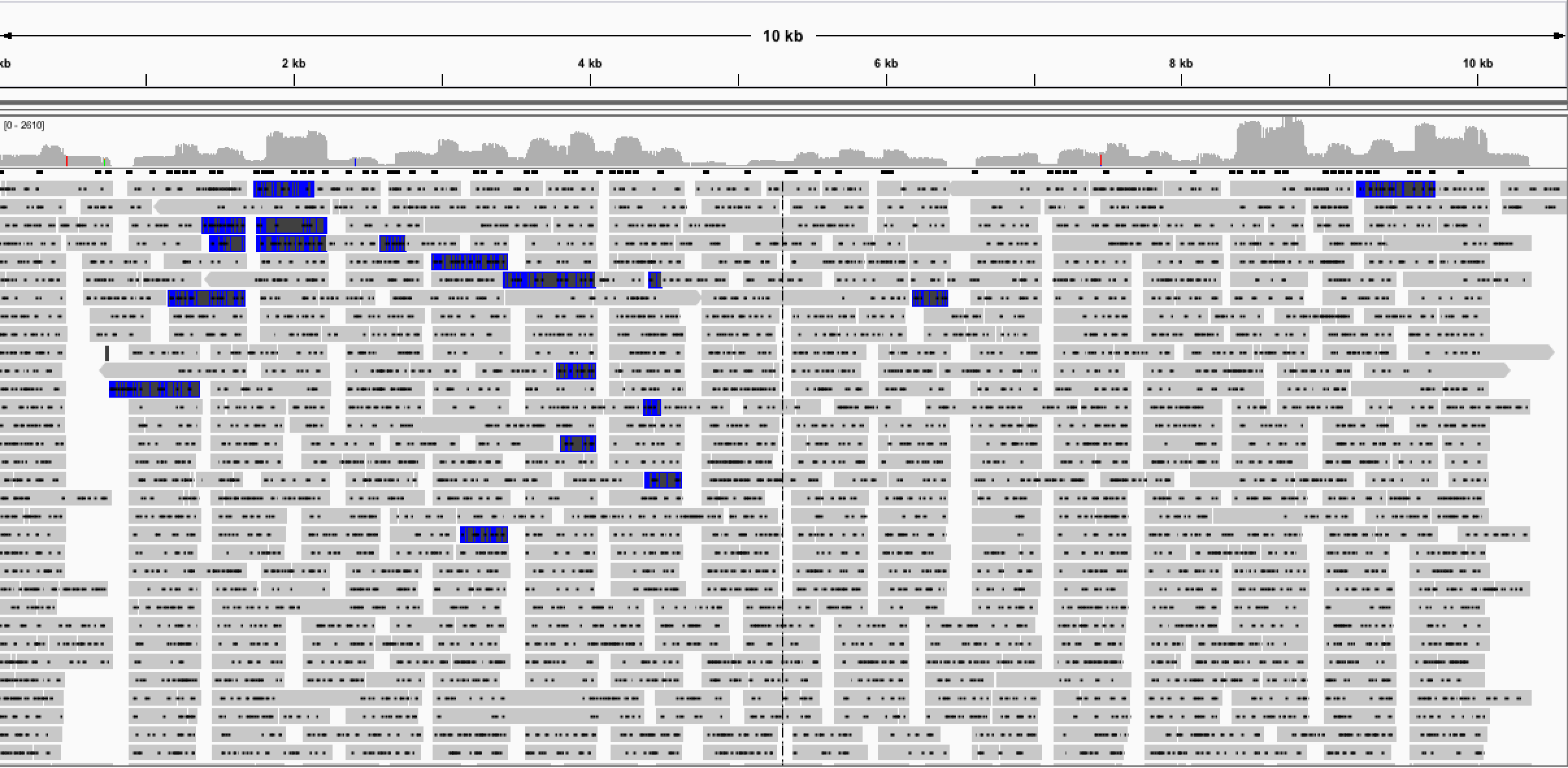

We began to notice problems with the primers almost immediately. Despite running the software on a multiple alignment of South American and African isolates we realised many primers had mismatches with respect the the African genomes. This wasn’t a major problem as we were expecting to find only South American lineage isolates on the road trip in Brazil. The next more significant problem was a large difference in Tm’s found between the primers. Despite specifying a minimum of 63°C, I found primers in the scheme with Tm’s between 43°C and 73°C. One of the old PCR rules of thumb is that primer pairs should have annealing temperatures within 2°C of each other so it looked like many of the primers wouldn’t be useable at all. Upon arrival in Saõ Paulo the first time, we initially had good results with singleplex reactions from the 400 bp scheme generating 70% coverage of the Zika genome with 38 amplicons.

Fig 1. Results of single-plex PCR scheme.

However it was a multiplex scheme we wanted and when combining primer pairs, initially in 8-plex we got very little amplification. I started writing a script to rationalise the choice of primers from our choice primers, starting with Tm and %GC I used pairwise2 (Smith–Waterman) from BioPython to find the primer position. I then screened out unsuitable primers and just about scraped together a scheme from the 450 available, however the maximum annealing temperature would be only 59°C, lower than I had hoped. With days to go before the road trip Ingra and I set up a 2-reaction experiment using the new scheme, the regions that failed to amplify we then split into two further pool giving 4-reaction (3 to 14-plex). If amplification was failing in some cases due to primer-primer interactions we thought by moving them into two new pools we may get them to work.

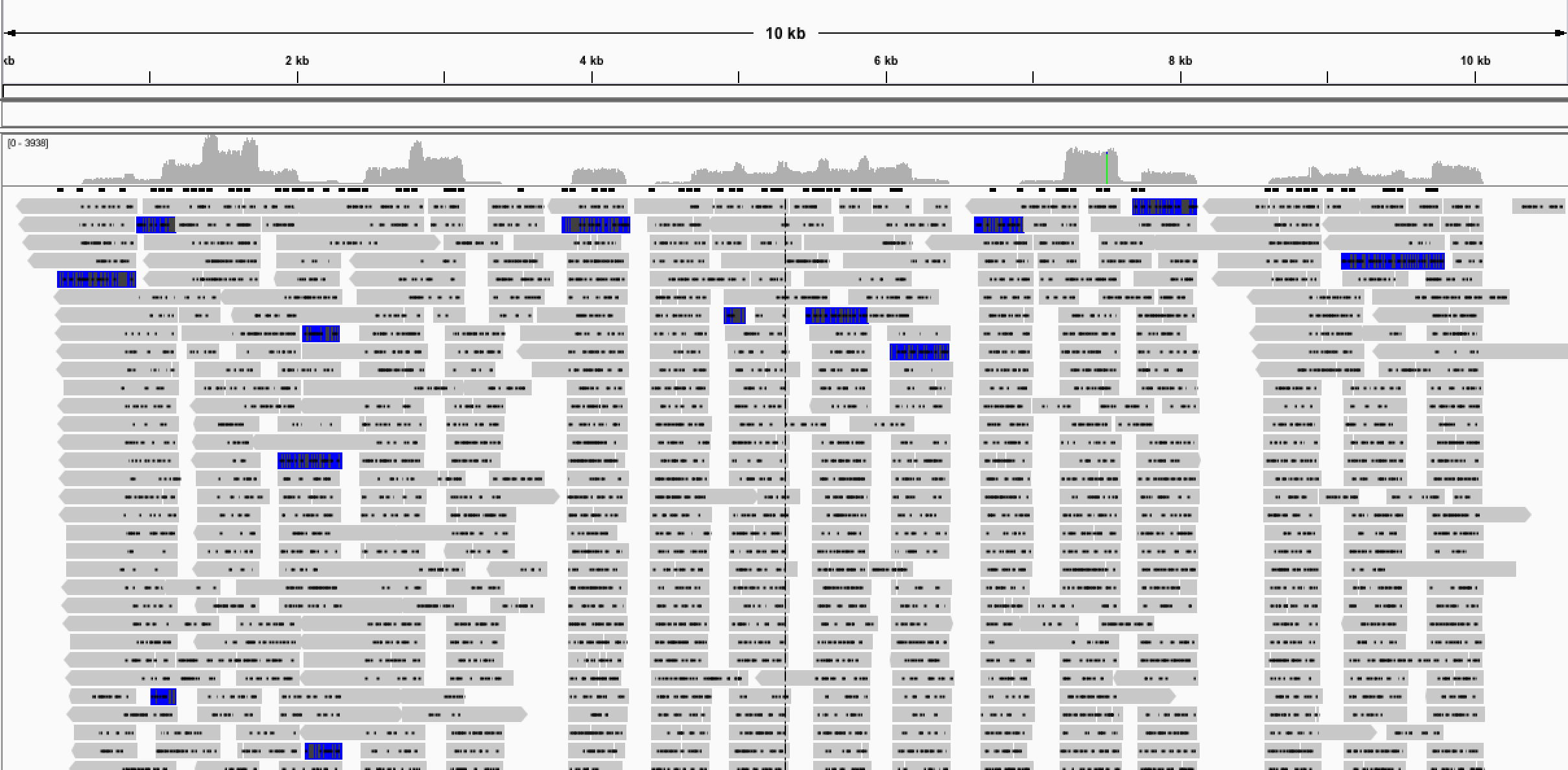

Fortunately for us and on the last possible attempt before the road trip we got our first decent genome from a sample known affectionately as sample 58, our low Ct test sample! With around 90% of the genome sequenced we were delighted to have sequenced our first Zika genome using the 4-reaction PCR scheme. We designated this protocol version 1 and it was this that we used or minor variants of it for the whole ZiBRA road trip.

Fig 2. Results of v1 multiplex protocol

The early sequencing runs during the road trip were generally positive and generated a number of partial genomes, however Nick and I were starting to become concerned that we had a clear relationship between genome completeness and Ct value. It appeared that sample 58 was the best sample, with partial genomes generated for other samples with Ct’s in the 20’s with very little specific Zika amplification for samples with a Ct over 30. In addition to production runs we performed multiple optimisation runs titrating all components of the PCR reaction mixture; Mg2+, dNTPs, DNA polymerase and primers. Generally altering the reaction conditions had either a neutral or negative effect. By increasing the primer concentration it appeared we could increase non-specific amplification unfortunately however it did not appear that reducing the concentration could not completely mitigate it.

After returning from the trip I became convinced we needed to design a fresh scheme implementing everything we had learned about multiplex PCR so far. I started writing what would become Primal, a package which would automate the manual method of primer design using tried and tested tools rather than employing new algorithms based on k-mer matching or de Bruijn graphs to select primer candidates. Primal manages the amplicon lengths and overlaps required but uses Primer3 (https://pypi.python.org/pypi/primer3-py) to generate candidate primers from a single reference genome. It then uses pairwise2 to find local alignments between the primer candidate and any other reference genomes provided. Mismatches, in particular 3’ mismatches are penalised and the highest scoring pairs are returned as a scheme. An alpha version of Primal is now hosted on CLIMB and has a web interface thanks to Andrew Smith (http://primal.zibraproject.org/). New features including the ability to visualise primer positions, view all alignments and a primer dimer detector are on the way soon.

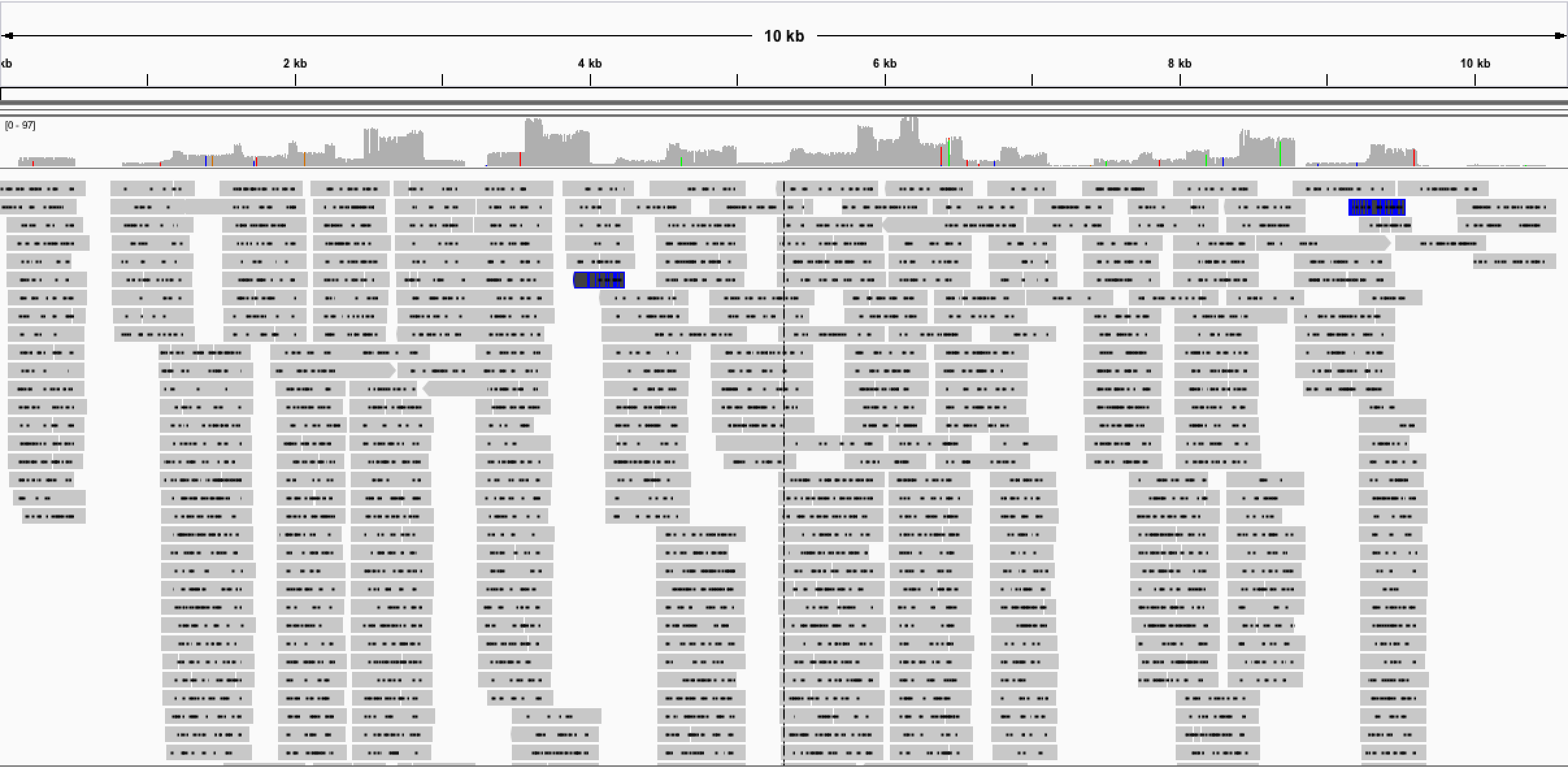

First indications of our v2 primers and protocol are very promising (available here), with complete genome coverage generated on our test material. Other groups using the protocol have reported success sequencing Zika from clinical samples up to Ct 36! We are currently in the process of rolling the new protocol out in Brazil and are doing our best to overcome the many logistical issues we have experienced. Watch this space!

Fig 3. Results of v2 multiplex protocol, coverage is better and more even.